An excerpt from the first chapter of my new book, Intertwingled.

When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe. – John Muir

I’m standing on an island beach in the northwest corner of Lake Superior. After nine hours in my Honda Civic and six hours aboard the Ranger III, my backpack and I have been transported into the wilderness archipelago of Isle Royale National Park. While this rugged, isolated refuge is among the least visited of our national parks, it’s well-known among ecologists for its wolf and moose, subjects of the longest continuous study of a predator-prey relationship in the world.

Of course, I’m not here as a scientist. I’m here to hike. But I was drawn to this place by the story of its ecosystem. When the study began in 1958, well-established mathematical models of predation described how the populations should rise and fall as part of a cyclical, co-evolutionary pattern that maintains the “balance of nature.” For the first few years, things proceeded as expected. But the ecologist, Durward Allen, had the foresight to persevere beyond the normal period of observation, and the dramatic, dynamic variation that unfolded was an illuminating surprise.

The more we studied, the more we came to realize how poor our previous explanations had been. The accuracy of our predictions for Isle Royale wolf and moose populations is comparable to those for long-term weather and financial markets. Every five-year period in the Isle Royale history has been different from every other five-year period – even after fifty years of close observation.

This is a lesson in humility, and a sign of what’s to come for those who labor in today’s high-tech ecologies. In user experience and digital strategy, there’s a lot of talk about “ecosystems” that integrate devices and touchpoints across channels. While this is a step in the right direction, our models and prescriptions belie the true complexity of our information systems and the organizations they are designed to serve.

Recently, while I was consulting with a Fortune 500 that does over $2 billion a year in online sales, one of my clients explained that over the years he’d seen lots of consultants fail to create lasting change. “They tell us to improve consistency, so we clean up our website, but the clutter soon comes back. We keep making the same mistakes, over and over.”

This infinite loop to nowhere results from treating symptoms without knowing the cause, a bad habit with which we’re all too familiar. Part of our problem is human nature. We’re impatient. We choose immediate gratification and the illusion of efficiency over the longer, harder but more effective course of action. And part of our problem is culture. Our institutions and mindsets remain stuck in the industrial age. Businesses are designed as machines, staffed by specialists in silos. Each person does their part, but nobody understands the whole.

The machine view was so successful during the industrial revolution, we find it astonishingly hard to let go, even as the information age renders it obsolete and counterproductive in a growing set of contexts. It’s not that the old model is all wrong. We’re not about to throw away hierarchy or specialization. But our world is changing, and we must adjust.

The information age amplifies connectedness. Each wave of change – web, social, mobile, the Internet of Things – increases the degree and import of connection and accelerates the rate of change. In this context, it’s vital to see our organizations as ecosystems. This is not meant figuratively. Our organizations are ecosystems, literally. And while each community of organisms plus environment may function as a unit, the web of connections and consequences extends beyond its borders.

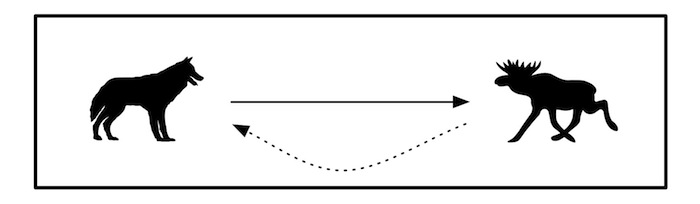

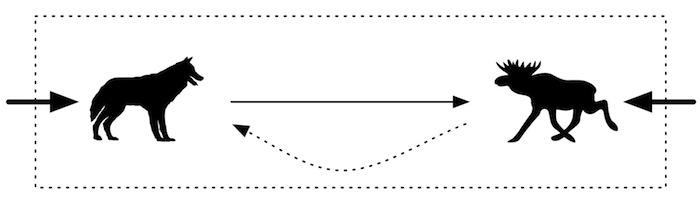

All ecosystems are linked. To understand any complex, adaptive system, we must look outside its limits. For instance, the story of Isle Royale is a lesson in systems thinking. In 1958, predictions for the rise and fall of populations were grounded in classic predation theory: more moose, more wolves, but more wolves, less moose, and less moose, less wolves, and so on. It’s an interesting, useful model, but it’s incomplete.

By 1969 the number of moose had doubled, a major shift in balance. By 1980 the moose population had tripled, then declined by half, and the number of wolves had doubled. Ecologists wondered whether the wolves might drive their prey to extinction. But two years later, the wolf population had been decimated by canine parvovirus, a disease that was accidentally introduced by a visitor who (illegally) brought his dog to the island.

Over the years, the moose population has grown steadily only to collapse due to cold winters, hot summers, and outbreaks of moose tick. The tiny wolf population failed to thrive for years due to inbreeding. But in the winter of 1997, a lone male wolf crossed an ice bridge between Isle Royale and Canada, and revitalized the population for a while. Today, however, the wolves are again at risk of extinction, and scientists fear that due to global warming, no more ice bridges will form.

What’s interesting for our purposes is that the surprises in this story result from exogenous shocks. They come from outside the model of the system. In ecology and economics, such disruptions are often explained away as rare, unpredictable, and unworthy of further study. But that’s an ignorant, dangerous conclusion. The truth is that the model is wrong.

We make this mistake over and over in the systems we build. We work on websites as if they exist in a vacuum. We forge ahead without mapping the ecosystems of users and content creators. We measure success and reward performance without knowing how governance and culture impact individuals and teams. We plan, code, and design wearing blinders, then act surprised when we’re blindsided by change.

If we hope to understand and manage a complex, dynamic system, we must practice the art of frame shifting. When our focus is narrow, our ability to predict or shape outcomes is nil. So we must learn to see our systems anew by soliciting divergent views. And when we uncover hidden connections, information flows, and feedback loops that transgress the borders of our mental model, we must change the model.

In the era of ecosystems, seeing the big picture is more important than ever, and less likely. It’s not simply that we’re forced into little boxes by organizational silos and professional specialization. We like it in there. We feel safe. But we’re not. This is no time to stick to your knitting. We must go from boxes to arrows. Tomorrow belongs to those who connect.

If this talk of change disturbs you, that’s good. Learning makes us all uncomfortable. When faced with disruption, we’re tempted to turn back. But if we press on, we build skills and understanding that may prove invaluable to us in the future. Once we overcome our initial fear and discomfort, we may even begin to enjoy ourselves. Some of life’s best paths start out on slippery rocks. Or at least that’s what I tell myself as I stand on the beach of Isle Royale, with my backpack, map and compass, anxiously gnawing on a hunk of meatless jerky.

It’s not that I’m afraid of the wolves. There aren’t many left. I’m worried because I’ve never been backpacking. My hikes always end in hotels. The last time I slept in a tent was at Foo Camp, a hacker event during which attendees camp in an apple orchard behind the offices of O’Reilly Media. And I couldn’t sleep. I was cold. My hips hurt. That morning, shivering in my tent but grateful for the orchard Wi-Fi, I fired up my Apple MacBook Pro and booked a hotel. But now, I’m headed into the wilderness alone, for four days and four nights. I’m 44 years old, and this is my first time.

Of course, it’s my own fault. Since turning 40, I’ve been making myself uncomfortable on purpose. At an age when it’s easy to fall into a rut, I’ve run my first marathon, tried the triathlon, and tackled new consulting challenges that terrified me. Now, I’m writing and publishing a book, and carrying a bed on my back. And I invite you to join me in discomfort. Because it’s not just my age. It’s our age. It’s the information age, a time when learning how to learn (and unlearn) is central to success. Instead of hiding from change, let’s embrace it. Each time we try something new, we get better at getting better. Experience builds competence and confidence, so that we’re ready for the big changes, like re-thinking what we do.

by Peter Morville

To continue reading Intertwingled, download chapter 1 (PDF) or buy the book. Thanks!