It’s a tough time to be a teacher. The bureaucracy is stifling. The politics are worse. And, the irresistible force of disruptive innovation has come to school. Everywhere you look, entrepreneurs sell silver bullets that will save our kids from the assembly line. Some teachers quit. That’s understandable but sad, because while the system must change and technology will prove transformative, when the dust settles, teachers will continue to serve as the keystones of our educational ecosystems.

The information age has produced an exhilarating array of pedagogical ideas and tools, yet despite all the revolutionary talk about computers and constructivism, the monolithic lecture is still the norm. We know this is wrong. Students have diverse interests and motivations and learn in different ways. The one thing they share is a 15 minute attention span. The lecture has value, but it must be short and is just a part of the whole. Teachers must weave conversation, inquiry, and performance into “architectures of learning” that meet the needs of each class.

This act of synthesis is hard. Technology won’t save the day, and teachers can’t cross the chasm alone. Designers, developers, publishers, and librarians are just a few of the folks needed to build these cross-platform services and structures for learners. And those of us outside the schools can’t wait to be invited. We must crash the party. So, in the spirit of transgression, let’s now explore the perilous intersection of technology, pedagogy, and the future of education.

The Whole Game

In Making Learning Whole, David Perkins argues convincingly that “playing the whole game” is vital to motivation and understanding. He begins with a childhood story about playing baseball, which he then contrasts with the “elementitis” of his formal education.

When I was playing baseball, most of the time I wasn’t playing full-scale, four bases, nine innings. I was playing a perfectly suitable junior version of the game…But when I was studying those shards of math and history, I wasn’t playing a junior version of anything. It was like batting practice without knowing the whole game. Why would anyone want to do that?

Once we’ve played the whole game, we’re motivated to build discrete skills. We’ll practice throwing, catching, and even running, because we understand how this work makes us better at something that matters.

Clearly, this is an important lesson for teachers. But it should also be taught to technologists. For instance, I was struck by the absence of the whole in this Khan Academy video about calculating the area of a circle. It explains how, but not why. To their credit, the folks at Khan are making progress on their library’s search and navigation systems, but I hope they’ll keep refining the information architecture of the tutorials themselves. In particular, I’d like to see a bit of the whole in each part. This sounds like a job for Vi Hart.

Inquiry Learning

Direct instructional guidance is defined as “providing information that fully explains the concepts and procedures that students are required to learn.” We often experience direct guidance as lecture plus textbook. At the other end are constructivist theories such as discovery and inquiry-based learning which emphasize the active role of learners in constructing knowledge for themselves. Students are invited to ask questions, try experiments, perform research, and solve problems.

A mix of methods works best. The optimal balance depends upon the teacher, the students, and the subject. But all too often, teachers cling to the long lecture. It’s safe and familiar, and they’re unsure what else to do. Efforts to break this bad habit take myriad forms. Mimi Ito spreads new media literacy beyond the geek elite with connected learning while Aleta Margolis transforms teachers from information providers into instigators of thought. Though they vary in approach, both share in the belief that the teacher-student relationship is essential to success.

This brings us to the MOOCs which promise to revolutionize education with free online courses for everyone. Since each class offered by Coursera, Udacity, or edX may include thousands of students, it’s fair to say there’s not much of a teacher-student relationship. To be fair, they do incorporate pedagogical techniques such as forced retrieval and peer assessment. But compared to an old-fashioned class with a teacher and 15 students, a massive open online course simply isn’t as good.

Of course, according to innovation theory, this initial inferiority is to be expected. In Disrupting Class, Clayton Christensen explains why and how the MOOCs will win. They must first compete with nonconsumption by meeting demand outside the schools (e.g., developing countries, home-schooling) and then within (e.g., letting students take courses not offered by their district). Later, this self-paced, student-centered model may gain sufficient momentum to become the dominant paradigm.

That said, there’s something the MOOCs are missing. Remote students lack access to a library and its online resources. Faculty may offer a few links for recommended reading, but mostly you’re on your own. Students do not have access to much of the scholarly literature in their field. This is a major obstacle if you put any stock in learning by inquiry.

This is also a serious opportunity. If Coursera, for instance, can work with academic libraries and publishers to offer its students access to scholarly articles and ebooks, it will enjoy a real competitive advantage, especially if it integrates a single search box, faceted navigation, and web-scale discovery into a search service that beats Google Scholar.

The Architecture of a Class

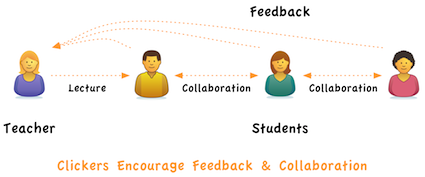

The best place for architects of learning is in the classroom, where changing structure changes lives, and even tiny interventions make a big difference. For instance, the use of clickers improves teaching and learning by providing immediate feedback, boosting attention, testing comprehension, and encouraging peer-to-peer collaboration.

Another structural shift is the flipped classroom – lecture at home, homework in class – which lets students get problem-solving help from their teacher and peers, and opens the door to “guest lectures” in the form of video tutorials from Khan Academy and the MOOCs.

A growing number of classes aren’t in a classroom. For instance, I’m on the advisory board of SJSU SLIS, a library science program that’s 100% online. Interactions between teachers and students are mediated by a learning management system such as Blackboard, Moodle, or Canvas. Some instructors roll their own which is wonderful because the LMS information architecture shapes the quality of the academic experience.

In fact, the LMS is ground zero for the future of the academic library. If these libraries hope to remain relevant, they must provide information and services at the point of need. Embedding librarians and LibGuides is a good start, but what’s most critical is an embeddable search widget. Students must have a quick, easy way to search the literature that’s relevant to their subject. So far, libraries have failed to meet this challenge. Discovery tools such as Summon and EDS come close, but coverage is spotty, and they lack support for local customization.

Getting this right is not just important for libraries. A universal search and discovery service that makes it easy for students to find answers from trusted sources is vital to the whole enterprise of learning and literacy. It transforms the LMS into a mission-critical bridge that connects direct instructional guidance to inquiry-based learning.

And this bridge should exist in every classroom. It makes no sense to limit the LMS to online education. Every class can benefit from a learning management system that offers online assessment and analytics, and that connects students to their teachers, and their peers, and to trusted sources of information. The LMS is the point of need where an “architecture for learning” can have the greatest impact.

Learning and Literacy

We watch lectures on iPhones, read textbooks on Kindles, run with Nike+, and sleep with Fitbit. We monitor markets with Orbs and energy use with Nest. We learn to code for free with Codecademy, and play with blink(1) for fun. And we learn what to learn next with Twitter.

But there’s a problem with this future of learning that exists today. It’s unevenly distributed. While some of us embrace the era of cool tools, many are left behind. Some can’t afford the entrance fee. Others can’t find the front door. There’s a literacy gulch that must be spanned, and tablet airdrops won’t do the trick. It’s not only about access.

Information literacy – the ability the find, evaluate, create, organize, and use information from myriad sources in multiple media – is the basis for lifelong learning. It’s increasingly important in every aspect of our lives from shopping and entertainment to healthcare and finance. And yet, most people, young and old, lack the requisite skills and understanding.

Let’s explore one tiny example. Our girls often ask for help with their homework, yet I’m easily stumped by middle school math. When I go to Google, they tell me they tried that, but I always find what we need. I’m not better at math. I’m better at search. And that’s why I’m able to help. But not all parents are librarians, so many kids must stay stuck.

The cure for information illiteracy should start in our schools. A quick visit to the library for bibliographic instruction is totally insufficient. This subject demands credit-bearing classes in both K-12 and college. It should also be woven deeply into the fabric of history, literature, math, and science class. To be effective, we must also teach the teachers.

Of course, education doesn’t stop in school. Today, all of us are continuously learning how to learn. In The Lean Startup, Eric Ries tells how entrepreneurs can learn faster than ever: who are our customers and what do they need? In The Participatory Museum, Nina Simon shows how to enlist visitors in acts of creation and critique that generate conversation and community. Quite often, the best ways to learn are low-tech. For instance, the awesome box is awesomely simple, and the brown bag is the best knowledge management system around.

Finally, for those of us who work on the web, there are opportunities to forge beyond findability by designing for understanding. Web 2.0 taught us how to engage users in acts of co-creation. Now, we must apply that lesson across channels, reaching out to teachers, librarians, social entrepreneurs, and anyone else who will work with us to build bridges.

We cannot get from here to there by only improving the parts. It’s not simply about better teachers or better tools. Success requires synthesis of technology and pedagogy. It’s about the integration of physical and digital. It’s about structural design that’s infused with systems thinking.

None of us can do it alone. While teachers will continue to serve as inspiration architects, we’ll also need information architects. Designing maps and paths in support of inquiry and co-creation is no easy task. We must blueprint before we build. Getting this right is the challenge of a lifetime. The architectures of learning we create together will shape the beliefs and behaviors of our children, our colleagues, and ourselves. It won’t be easy, but it will be worth it. Let’s get learning!

by Peter Morville