This is an edited transcript of a talk I had the privilege of giving at World IA Day (video) and at the IA Conference (vimeo, ppt, otter). Questions and suggestions (@morville) are welcome.

Hello! I’m Peter Morville, and I’m so happy to be able to speak with you about gentle change. This is a personal talk, and to understand where I’m going, you’ll need a sense of where I’ve been.

In the early 1990s, I went to library school at the University of Michigan, where I fell in love with the Internet. And I had a dream. I wanted to organize information so people could find what they need. And that’s precisely what I’ve done. Over the last 25 years, I’ve helped all sorts of organizations with their information architecture and user experience challenges.

Along the way, I’ve written a number of animal books about information architecture, findability, search, systems thinking, and planning. Implicit in all these books is the idea of change; and the hope that with greater understanding, we can make better websites, better systems, and better plans. In 2003, I had the opportunity to make the cancer.gov website better. We improved the information architecture, and we made the site and its content more findable. We had a wonderful team, and a sense of purpose, and it was a great experience. A few months after launch, my client received a message which I’d like to read to you now.

In 2003, I had the opportunity to make the cancer.gov website better. We improved the information architecture, and we made the site and its content more findable. We had a wonderful team, and a sense of purpose, and it was a great experience. A few months after launch, my client received a message which I’d like to read to you now.

Last evening I learned my 72 yr. old mother has lung cancer. Still in a state of shock she was not able to provide me with much information. She lives four hours from me, and I am unable to be with her at this moment due to work obligations. So until I can be with her, I am taking the time to learn as much as possible on the subject of lung cancer. So I would like to thank the person or persons for this very informative web site. This web site has given me the information on how I as a daughter can help my mother and also teach my family what to expect in the coming months. Thank you!

This is why I became an information architect. This is why I fell in love with the Internet. This was the realization of my dream.

That feels like a lifetime ago. So much has changed. In the intervening years, we’ve discovered the dark side of the Internet; and my dream has mutated into a nightmare.

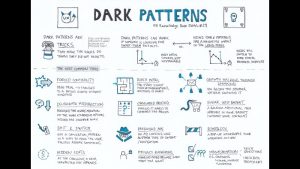

Misinformation, roach motels, privacy zuckering, and other dark patterns are rampant. We’ve learned the hard way that change isn’t always for the better.

Now, I’ve been fortunate to have only a few clients who rely on dark patterns (and in those cases, I was asked to help them kick the habit). But, in my consulting work, I’m often disappointed by an absence of ”compassion for the user.”

This didn’t matter in the early days, because we were mostly left alone to do good work. But it matters a great deal now that the web is mission critical, the business is engaged, profit is the motive, and our work is political.

As a result, many user experience teams have fallen into a state of learned helplessness. And those who are willing to fight for their users, often lose to more powerful stakeholders and interests. These days, in many ways, it’s never been harder to practice compassionate design. This is a deep cultural problem. There is no quick fix. And it makes me sad.

So I’ve been planning my escape. I have a new dream. It’s called Sentient Sanctuary. I want to create a gathering place that’s dedicated to more happiness and less suffering for all sentient beings. This is how I hope to spend my next 25 years. I can’t tell you exactly how this vision will unfold. I can’t show you a plan or a schedule. But I can assure you, there will be goats.

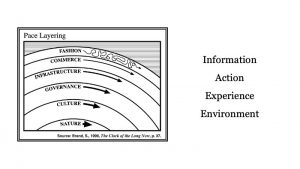

Of course, I haven’t given up on this community, and that’s why I’m giving this talk. I’m hoping we can bring these dreams together. To make our cultures capable of compassion for users, we might learn from those who work to grow compassion for animals. From humane societies and sanctuaries to undercover investigations and shock advertising, the diversity of their strategies is impressive. Our community is in its infancy. We’ve barely begun to try to change culture. We have so much to learn from them. So let’s explore 4 ways of change – information, action, experience, and environment – and see how these strategies apply across contexts.

The caw of a crow is noise to us but information to her friends. Information is data that makes a difference. But, isn’t a signal still a signal, even without a receiver? We struggle to define information, yet we use it all the time; to learn, to understand, to teach. Information is power. It changes who we trust, where we go, and what we believe.

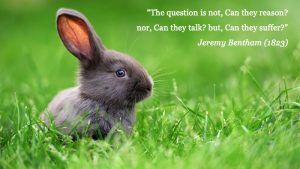

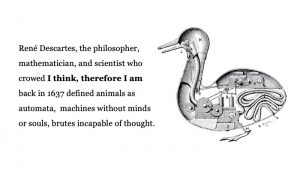

Information, in the form of language and classification, can be persuasive. In 1637, when Descartes crowed “I think, therefore I am,” and categorized animals as machines, it had a profound impact on our culture. It elevated thinking above feeling, separated humans from animals, and placed most sentient beings outside the moral circle. In 1823, two hundred years later, Jeremy Bentham pushed back, arguing “the question is not, can they reason, nor can they talk, but can they suffer?” And yet, in his choice of pronouns, we see that the false dichotomy of us and them had already become embedded in our culture.

In 1823, two hundred years later, Jeremy Bentham pushed back, arguing “the question is not, can they reason, nor can they talk, but can they suffer?” And yet, in his choice of pronouns, we see that the false dichotomy of us and them had already become embedded in our culture.

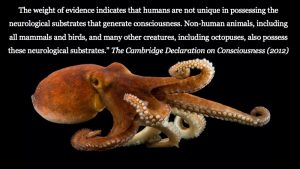

Of course, science keeps discovering the inconvenient truth that we have more in common than we care to admit. In 1871, Charles Darwin famously argued the difference in mind between human and non-human animals is “one of degree and not of kind.” In 2012, Stephen Hawking joined an international group of neuroscientists to declare that non-human animals experience consciousness. In short, we are all sentient, we all think and feel, because we share brain structures, body chemistries, and ancestors.

In 2005, when our oldest daughter Claire was 6 years old, a dog named Knowsy entered our lives. Now I was raised to believe dogs don’t belong on couches or beds. But Claire believed I was wrong, and incessantly violated my rule. One day we had a big fight. So Claire’s in her room, on the floor, her back against the wall, crying. I’m trying to explain why dogs don’t belong on beds, when Claire looks me straight in the eye, and declares “Knowsy is a person too!” And that was the end of the argument. From that point on, Knowsy enjoyed the consequences of her classification.

I could go on. There are so many arguments. I have so much to say. But that’s the problem. In using information to effect change, the risk of overload and anxiety is high. So let’s look at three more examples, and then we’ll move on.

There’s a nonprofit, Faunalytics, that helps people help animals by organizing and sharing data. These are the quantitative analysts of the animal rights movement.

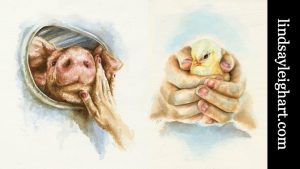

It’s interesting to contrast their approach with the work of Lindsay Leigh Lewis, an activist who uses art to engage emotions on behalf of animals. When Lindsay showed her painting of this pig to her mom, her mom became a vegetarian, on the spot. Art changes people. It’s a uniquely powerful kind of information.

And then there’s PETA. As the world’s largest animal rights organization with annual revenues of $50 million, they are clearly effective at using information to attract attention and money. Of course, what’s more important but harder to measure is the lasting impact of their advocacy. What are the second and third order effects? PETA takes a distinctly un-gentle approach to change, and I worry about the backlash they engender.

So, how might we adapt these strategies to grow compassion for users? Well, for many of us in this community, information is our addiction, and we use it all the time. We routinely deploy analytics, user research, and personas to engage stakeholders’ hearts and minds. And it works. To a degree. But these days, information immunity is high. People tend to believe what they want. Increasingly, if we hope to break through, we need to explore different strategies.

One day, an old man was walking along a beach littered with starfish washed ashore by the high tide, and he came upon a young boy throwing them back into the ocean, one by one. Puzzled, the man asked what he was doing. The boy answered, “I’m saving these starfish.” The old man chuckled, “Son, there are thousands of starfish and only one of you. What difference can you make?” The boy picked up a starfish, gently tossed it into the water and replied, “I made a difference to that one!” This story is old, so why read it now? I’ve written a verse to explain.

I struggle with this parable.

I’m not sure who I am.

Yet, the wiser I grow,

the less I’m like the old man.

And now I ask for your patience, as I follow my poem with a prayer.

God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, Courage to change the things I can, And wisdom to know the difference.

Change is hard. It obliterates, and is the only path to, serenity. We fear we can’t change ourselves or others, and yet we can’t stop trying. We fear our situation is hopeless. And yet, time and again, we act.

There’s an elephant sanctuary in Tennessee you can’t visit. For 25 years, it’s been providing captive elephants a safe haven in which to live out their lives. Globally, elephants are on the path to extinction, and nobody knows how to save them. It’s all too easy to give up or look the other way. But there is wisdom in the work of the sanctuary. When it seems that nothing will solve the problem, the right action is to do something.

I walk dogs once a week at the humane society. It’s an activity that can involve fear. When I step into an enclosed kennel, the dogs I’m most afraid of are the dogs most afraid of me. Yet they often turn out to be my favorites. When the savage pit bull rolls over in the grass and asks for a belly rub, it melts my heart. It takes courage to take action, but it feels good to be making a difference, even when it’s just one dog at a time.

I once worked with a community college to improve their website. We did user research and learned what students cared about most were the course registration system and the faculty directory. Those two resources were the most important and worst designed. I explained this to the executives, and the president said, “yeah, we’re not going to touch those.” They had outsourced registration. Change was expensive. And the faculty directory was politically sensitive. So, we made the rest of the website awesome, and the project was a success. And I believe that was the right thing to do. Because, most often, the best use of our energy is to change the things we can.

We act by changing the things we can because we know “you can’t change other people.” Or, to be precise, it’s really hard to change other people. You have to engage in difficult conversations where mutual learning is the goal. You have to listen. You have to understand. And you have to be willing to change yourself.

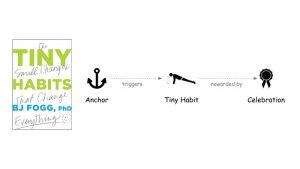

And we all know it’s not easy to change ourselves. But, as BJ Fogg has been telling us for years, it is possible if we start with tiny habits.

This works because, mostly, belief is shaped by behavior, and not the other way around. That’s why small wins are so valuable. A few tiny steps in the right direction make us believe we can go the distance.

A few years back, I hiked the Grand Canyon rim to rim. It took a lot of tiny steps. So, I’m walking along the bottom of the canyon, and I’m gazing up at the beautiful rock formations that are two thousand million years old, when I hear a rattle. I froze, looked down, and noticed I had just walked past this rattlesnake. This is the second photo. The first is blurry because my hands were shaking. For the next few hours, as I continued my hike, I was fearful and jumpy. I was sure every rustle was a rattle. And then I had an epiphany. We fear and kill them more than others, because we notice them more than others, because they warn us with their rattle. In that moment, my ignorance gave way to understanding, and my fear transformed into compassion. And that is the power of experience.

Rabbits, hamsters, a dog, and other animals helped Ellie Laks survive the abuse and trauma of her childhood years. So, when she grew up, Ellie created Gentle Barn, a place of healing for animals and children. Because sometimes the best therapy for a hardened teenager is to let them spend time with a chicken or a horse or a cow.

Our youngest daughter Claudia and I visited Best Friends Animal Sanctuary in Utah. It’s not far from Zion National Park. We got to walk a pig named Cherry. She was strong, smart, sassy; and when we reached the end of the path, she didn’t want to go back. Let me tell you, that was quite an experience.

And so was my visit to Mission: Wolf in Westcliffe, Colorado, where I met this wolf named Zeab. So, we go into the enclosure, and we sit down on a log, and three wolves approach. Now, you can’t tell from the photo, but Zeab is enormous. And wolves have a very special way of saying hello, and it’s both rude and dangerous to try to avoid this greeting. So, let me simply say, few experiences are as memorable as being licked on the mouth by a wolf.

Now, I don’t mean to suggest we should be nearly so intimate with our users. But it does help to spend time with them. There is nothing so powerful as face to face. There is no substitute for difficult conversations. This goes for executives too. It’s not good enough to read the report. They must be in the room. They must be part of the conversation. If we want executives to care about users, they must actually have the experience.

I don’t have many heroes. Kathy Sierra is one. As co-creator of the Head First series of books published by O’Reilly Media, Kathy pioneered a better way to teach programming. But she became a target of harassment, doxxing and death threats, and so in 2007, she left the tech world for good. In the ensuing years, Kathy reinvented herself by starting Intrinzen, where she’s pioneering better ways to motivate and rehabilitate horses. Instead of traditional training methods which are centered on the use of force, Kathy designs the environment. She uses grassy slopes, piles of sand, and the presence of other horses to make it easy for learners to do the right thing.

The Nonhuman Rights Project aims to change the common law status of animals from things to persons. In 2018, they secured the world’s first Habeas Corpus Order on behalf of an elephant. This means a judge agreed their client, Happy, an elephant at the Bronx Zoo, has the right to bodily liberty. The leaders of the Nonhuman Rights Project understand that changing the law is a powerful way to change the environment. They also know this is a heavy lift. These folks are playing the long game.

In the meantime, there’s vegan pizza…

And, the Kentucky Fried Miracle of Beyond Fried Chicken.

And the Impossible Whopper. And the list goes on…

I believe that plant-based meats, eggs, milks, and cheeses together with cellular agriculture will change our relationship to animals forever. These foods will make it easy for us to do the right thing. It’s still necessary to organize and share data and to make the case for ethics and empathy. But those strategies are insufficient, because environment eats information for lunch.

We are drawn to information architecture because we understand the power of environment. As the architects of places made of information, we know the value of context. But that doesn’t mean we have the capacity or courage to change what matters. All too often, we are content to hack at the branches, rather than strike at the root. What’s the change to environment that would most help your users? I hope you’ll reflect on that question.

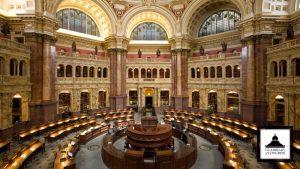

When I worked with the Library of Congress, I wasn’t gentle. I wrote a report, an evaluation of the Library’s web presence, that was brutally honest. And when I went to DC to deliver my findings, I learned my report had been placed under embargo, and my meetings had all been canceled. Eventually, my report made its way to the Executive Committee, and, at the highest level of the Library, they decided “we must change how we work on the Web.” They formed a Web Governance Board, led by the Chief of Staff, and they asked for my help. And together we made real progress. I’m proud of the work that we did. But we didn’t achieve nearly as much as I’d hoped, because we failed to wrangle with culture. And the backlash was fierce. We were undermined by the Congressional Research Service, ignored by the Copyright Office, and I had the distinct privilege of being yelled at by the Law Librarian of the United States of America.

In our community, we use information to act on behalf of users. We tackle interface, infrastructure, and governance. Occassionally, we design experiences for stakeholders. But do we dare to change the environment? Do we question the values and assumptions of our culture? Do we even know what they are?

As designers and information architects, we make the invisible visible. We’ve done it for websites and software. Now it’s time to shine our light on culture. I’m done with user-centered design, because we are all inside the moral circle. There are no externalities. Everything is deeply intertwingled. I’m an advocate for un-centered design, because we are all equal. And, because we are running out of time. So I mean it far more inclusively than Benjamin Franklin, when I say… “We must, indeed, all hang together or, most assuredly, we shall all hang separately.”

In the words of Steven Wise, ”any two beings are infinitely different and infinitely alike.” We choose whether to lump or split. And, how we classify reveals more about ourselves than about what we classify.

As George Lakoff told us “categorization is not a matter to be taken lightly.” There is nothing more basic than categorization to our thought, perception, action, and speech.

As we learned in Sorting Things Out… Each category valorizes some point of view and silences another. This is not inherently a bad thing – indeed it is inescapable. But it is an ethical choice, and as such it is dangerous – not bad, but dangerous.

Robin Wall Kimmerer, a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, reminds us our way is not the only way. Most indigenous peoples do not draw the moral circle as narrowly as we do. They perceive the ecosystem as a community of sovereign beings, inhabited by subjects, not objects. What will it take to shift our culture in the right direction? I don’t know. I don’t have the answers. But I do know we won’t get anywhere unless we wrangle with language and classification.

We know how to narrow the moral circle. Every genocide is preceded by the reclassification of people as animals or insects, and by the threat of contagion.

We’re less confident in our ability to expand the moral circle. Mindfulness is the closest we’ve come. And please understand, meditation isn’t only about inner peace. As Pema explains, “the bodhisattva vow is to work on ourselves so that we can be effective instruments for social change.” In other words, we must secure our own oxygen masks so that we can help others.

I don’t know how to mend our culture, but I do know Gandhi was right. There is the same connection between the means and the end as between the seed and the tree. How we do what we do matters. This brings us to gentle change.

Last summer, I spent time at a place called Happy Hooves. My teacher, Sara, was inspired by Kathy Sierra to experiment with better ways to teach horses. We worked on positive reinforcement in which the horse performs tasks for treats. But here’s the twist. Sara placed a bundle of hay nearby as a second source of food. This lowers the pressure. The horse need not perform to eat. And it worked. When our horse tired of learning, he wandered away from us to munch on hay. And then, having had a chance to relax, he chose to come back and continue the lesson. I’m inspired by Sara’s example of being gentle. If we’re patient, persistent, and kind, we will find a better way.

Moving fast triggers fear. We are all dangerous when scared. And when someone makes us afraid, we neither forgive nor forget. That’s why the use of force doesn’t work, not really. There is no transformation without understanding and a change of heart.

Moving fast breaks things. It sows the seeds of fear, anxiety, trauma, and grief. What we need to break is the bad habit of moving fast. And we’re running out of time. The transfiguration of our assumptions and values will require the rebirth of ritual and ceremony. We must change how we think about life. We must change how we feel about death. And we are going to need courageous acts of information architecture. Because we are all at the mercy of language and classification.

There’s a debate among academics and activists about whether the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park changed the flow of rivers and restored balance to the ecosystem. In our complex world, it’s so hard to find truth, so easy to lose trust, so tempting to give up. So what can we do?

Well, we can start by being honest about our own ignorance, vulnerability, and fear. And we can take tiny steps carefully; we can balance compassion with humility; we can practice gentle change. But please don’t mistake the speed or size of our step with the urgency, gravity, or magnitude of our goal. We go slow to do less harm, and to learn from mistakes; so in the long run we can go the distance.

So, start with your users, because humans are people too. But don’t stop there. The arc of our moral universe must bend towards more happiness and less suffering for all sentient beings. We are all stardust. We are all in the circle, together.

And that’s all I have. Thank you for your attention!

by Peter Morville