My new book is about planning for everything from websites to weddings. My workshop and this article focus specifically on how to plan for design and how to explain why it matters.

I realized that why and how are inseparable.

We thought we’d closed the deal on a six figure, nine week project, when our client asked “what can you do in a week or two?” As the organization had recently shifted from waterfall to agile, he was under pressure to break the work into sprints. We explained an ability to “see the whole” is vital to information architecture, and then we reached agreement on a fast yet robust five week project.

Upon reflection, I noticed when I explain what I do, I assume the why and focus on how. This is a bad habit. I also realized that why and how are inseparable. It’s impossible to understand the value of planning for design without grasping the nature of the work. To argue for user research, content strategy, information architecture, and participatory design, we must integrate why and how.

In the 1990s, I’d explain that investing in information architecture improves findability, but I learned that to focus on one facet of the user experience is self-limiting. The pace layers argument is better. Our work in research and structural design endures (5 to 10 years) and impacts downstream activity (a stitch in time saves nine). Often it’s best to highlight benefits – a taxonomy will enable the enterprise to share and integrate data across silos, align business processes, deliver a coherent digital front-end, and improve customer satisfaction.

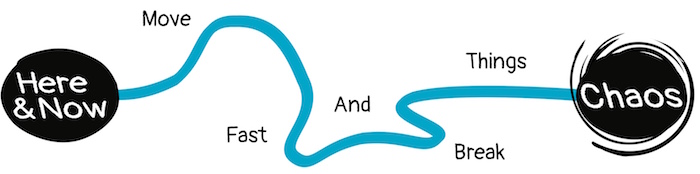

These arguments work, to a point, but it’s increasingly difficult to make the case for planning for design in a “move fast and break things” culture in love with quick fixes and vanity metrics. I’m sure I’m not alone in frustration. So, in search of better ways of framing the why behind what we do, I’ve asked some of the smartest folks I know.

Why to Plan (and How)

The first response was the shortest: “Planning takes time but saves much more time, with better results, in the long run.” It’s no surprise she’s been successful as head of design for Google and as operating partner at Khosla Ventures, where she gets startup CEOs to take the time for design. Irene Au speaks truth to power, concisely.

As Dan Brown asserts, designers must be confident.

An essential ingredient in the design process is confidence. Designers must feel confident about their decisions to propel the process. Confidence depends on good planning: by thinking through what you’re going to do and how you’re going to do it, you can be more confident about your approach and decisions.

– Dan Brown

Similarly, Abby Covert is direct in stating we must make sense of this mess.

Planning may mean setting aside what is innovative to pursue what is necessary. Too many organizations build their next cool feature on top of a crumbling infrastructure instead of taking time to plan a stable foundation. The pressure to “not plan, just act” is a plague sweeping the design and technology community; and we are making the world suffer the consequences.

– Abby Covert

Clarity is a great place to start, but we may need to reframe what we do to overcome the growing cultural resistance to understanding the problem as evidenced in the simplistic argument by Jason Fried that planning is guessing.

A mindset focused on the speed of the cycles has taken hold of business and has prevented any contemplative approaches.

– Indi Young

Indi Young has reframed her work brilliantly by making the distinction between problem space and solution space. Teams within organizations spend most of their time working on solutions in an iterative series of sprints, so it’s natural to want to integrate planning for design into this agile framework, but it won’t work, because problem space research is “the thing that does not fit.”

The problem space is about turning away from your solutions (products or services) and toward people, for a time, to soak up an understanding of the way people think their way toward a purpose.

– Indi Young

In contrast, Steve Portigal (who wrote the book on planning for improvisation in the context of user research) highlights the emergence of ResearchOps (like DesignOps and DevOps) as a way to build infrastructure so research can occur and impact design and product decisions at scale. By optimizing the operational details of research (e.g., how to find participants), ResearchOps helps research and design teams to boost speed, reach, impact, and quality.

The Trojan horse is efficiency. By building infrastructure, we lower barriers to entry and risk, so people can learn from experiments and be persuaded by examples of success.

– Steve Portigal

Steve’s thoughts align with those of Boon Yew Chew who argues planning must fit into culture to gain credibility and momentum, but that lean design may fail to scale. In the next larger system, the lens of the two loops model may reveal a way to escape old traps by embracing new options.

Organizing the Future

If engineers fail to plan, bridges collapse and people die. We are now learning the hard way that the consequences of bad software are no less dire. In Planning for Everything, I argue we must reject the false dichotomy of “act or plan” and instead find the balance of planning and improvising that’s a fit for each context. But I know this is an uphill battle as resistance to planning (and nuance) runs deep.

In my workshop, a lament that “our executives are allergic to planning” made heads nod. In a debate, Hillary delivered this zinger: “Donald just criticized me for preparing for this debate. And, yes, I did. You know what else I prepared for? I prepared to be president.” It was a great line, yet the chaos candidate won. It’s obvious a “move fast and break things” mindset is fomenting chaos on all levels.

We are in the void, near peak chaos, and that’s why I feel hope. This belief bubble is about to pop. We all know deep down that planning with intelligence and empathy is our responsibility. As Kyle Soucy reveals in this tearful story, it’s a lesson we learn as kids.

Forget it, Mom. It’s OK. I didn’t plan.

Those of us who know how to plan for design must get better at explaining why. And we must look for levers to extend and amplify our superpowers beyond the context of work. There are no externalities. So we must always be planning for everything.

I received more thoughtful responses from smart people than I could pack into one article, so to learn more about how to advocate for planning, see Why to Plan for Design (and How).