I follow a plant that tweets. Her name is pothos and she lives in Toronto with Angela, an information architect. When pothos is thirsty, she asks for help. Sometimes days pass before the water comes. Bruce Sterling once noted, “Futurism doesn’t mean predicting an awesome wonder; rather it means recognizing and describing a small apparent oddity that is destined to become a great commonplace.”

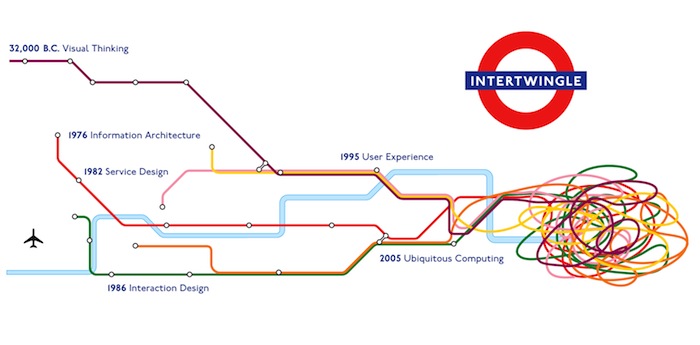

Well, I’d be willing to place a long bet that pothos is one such oddity, along with smart penguins, shoes, meters, packages, and robots. These proto-spime are harbingers of ubiquitous computing, an era we’ve been calmly awaiting since 1988 when Mark Weiser first described a world of invisible computers embedded in everyday objects.

So, the vision of an Internet of Things is nothing new, but the reality is something else. Nobody could have predicted the myriad ways in which information would blur the lines between product and service to create multi-channel, cross-platform, trans-media, physico-digital experiences. This is the complex reality that today’s executives and entrepreneurs must navigate. And while the archetypal ecologies of iTunes and Nike+ offer some insight, we’re mostly exploring new territory without a map.

Service Design

That’s not to say we’re starting from scratch. For instance, the practice of service design dates back to a 1982 article by G. Lynn Shostack entitled How to Design a Service:

The difference between products and services is more than semantic. Products are tangible objects that exist in both time and space; services consist solely of acts or process(es), and exist in time only. The basic distinction between “things” and “processes” is the starting point for a focused investigation of services. Services are rendered; products are possessed. Services cannot be possessed; they can only be experienced, created or participated in. Though they are different, services and products are intimately and symbiotically linked.

In this landmark paper, Shostack explores the relationships between products, services, people, and their environments. And, she explains the need for service blueprints that map both the potential (optimal) service and the actual (imperfect) rendering.

Key concepts include:

- Touchpoints. The tangible elements of a service, including everything that customers see, hear, touch, taste, and smell.

- Line of Visibility. Separates the “front stage” (visible to the customer) and “back stage” (tools, processes, infrastructure).

- Customer Journey. The experiences people have as they engage and interact with a service (or set of services) over time.

Decades later, these concepts remain relevant, and yet we must adapt for new contexts. As Glushko and Tabas explain, today’s “service systems” may include interrelated sub-systems (e.g., person-to-person, self-service) across multiple locations, devices, and channels; and customer satisfaction is “influenced by the extent of integration and consistency” across those channels. To manage this complexity, they suggest framing service encounters as information exchanges:

A key tenet in the service system perspective is that it emphasizes what is common to person-to-person services, self-service, and services where the provider and consumer are both automated processes rather than focusing on their differences. Each of these types of service encounters requires a service provider and a service consumer, and each provider has an interface through which the service consumer interacts to request or co-produce the service. This level of abstraction highlights the information requirements, inputs and outputs for the service, and the choreography with which the provider and consumer exchange information to initiate and deliver the service.

We’ll revisit “information exchanges” shortly, but let’s first explore an alternate framework that’s evolved largely apart from service design.

User Experience

In 1995, Don Norman joined Apple as a “user experience architect” and gave name to what’s become a cross-disciplinary practice that binds information architects, interaction designers, usability engineers, content strategists, and other user experience designers loosely together. In the early days, UX was defined narrowly as “user-centered design for the Web” but it soon became evident that a broader framing was required, since the experiences users have bridge multiple channels. Today’s more expansive definitions include:

User experience encompasses all aspects of the end-user’s interaction with the company, its services, and its products. – Nielsen Norman Group The design of anything, independent of medium or across media, with human experience as an explicit outcome and human engagement as an explicit goal. – Jesse James Garrett

Now, it’s worth pausing for a moment, to acknowledge that these definitions manifest an ambitious agenda that’s sure to ruffle some feathers. In the words of Bruce Sterling:

I’m interested in “experience design” because it’s the most imperialistic of all design disciplines to date. I mean, ‘design’ can be about pretty much anything, but ‘experience’ design – come on, what ISN’T an experience?

This begets the question: how can we strike a balance between mediumism and imperialism? The solution requires recognition that user experience is a practice led by T-Shaped People. None of us are experts across all media, but today’s environment demands a multi-channel, cross-media perspective. If we approach this challenge with courage, humility, and a willingness to collaborate with and learn from others, we can play an important role in helping people to design from the outside-in and create beautiful seams in today’s ubiquitous era.

In this effort, Mike Kuniavsky is already leading the way. His upcoming book Smart Things synthesizes ideas from myriad fields into a roadmap for what he calls “ubiquitous computing user experience design.” His framing of devices as “service avatars” within a hierarchy of experience scales (covert, mobile, personal, environmental, architectural, urban) embraces and extends the conceptual framework of service design.

Information Architecture

Smart Things also offers rich insights into the practice of ubiquitous information architecture design or pervasive IA. While Kuniavsky advises that we view information as one of many design materials (like wood and carbon fiber) from which devices can be made, he also highlights its role as “the core material in creating user experiences.” He goes on to discuss the use of information shadows that are made possible by RFID and other item-level identification technologies.

When a unique identifier is attached to an object, it becomes possible to collect the metadata about that object into a single information shadow. The unique identifier is the leverage point with which to access and manipulate the whole information shadow in relation to similar shadows.

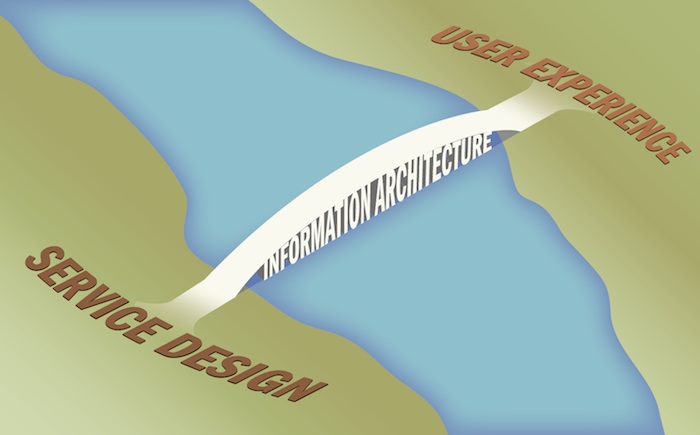

Unique identifiers or “handles” let us aggregate metadata across channels. This hearkens back to the earlier concept of “information exchanges” and invokes the potential of IA to serve as a bridge that connects user experience and service design in the ubiquitous era.

But, if we’re to fulfill this promise, we have much to do. For starters, we must develop a vocabulary that includes what Karl Fast calls “medium-independent conceptual constructs.” In other words, we need better ways of talking about information interaction across channels.

We’ll also need frameworks for choosing which features and modes of interaction to support across platforms and devices. How do we strike a balance between cross-channel consistency and channel-specific optimization? How can we make places that bridge multiple spaces? We already wrangle with these issues as we design experiences across websites and mobile apps, but that’s only a small piece of the puzzle. How can we inspire ourselves and our colleagues to see the big picture? For this, it’s worth looking back to the original definition of information architect, a term coined in 1976 by Richard Saul Wurman:

- An individual who organizes the patterns inherent in data, making the complex clear.

- The person who creates the structure or map of information that allows others to find their personal paths to knowledge.

- The emerging 21st-century professional addressing the needs of the age focused on clarity, human understanding, and the science of the organization of information.

In particular, there’s treasure buried in #2. As we venture into the uncharted waters of ubiquitous service design, we have a tremendous opportunity and responsibility to make sense by making maps, not just for users but also for our colleagues, our clients, and ourselves.

Experience Maps

In recent years, thanks to Dan Roam and Dave Gray, I’ve grown to appreciate the power of visual thinking. Blueprints, sketches, diagrams, and maps are invaluable knowledge tools that help us to look, see, imagine, and show. And thinking in pictures isn’t just for designers. Visuals are often the single best way to engage the attention of busy executives and entrepreneurs, because as Dave Gray explains:

A picture can connect the strategic with the tactical in a way no other communication form possibly can.

Well, I can’t imagine a context in more desperate need of visual thinking than the brave new world of ubiquitous service design. As information technology rapidly transforms the landscape, it’s absurdly difficult to keep up with what’s possible, never mind what’s desirable. If we’re to design coherent multi-channel services and experiences, we must add new visuals to our toolkit.

For starters, we should complement service-centered blueprints with user-centered maps that show the full array of choices and channels that people navigate every day. Along these lines, Jeffery Callender and I are experimenting with experience maps that show, for instance, the myriad options people have when looking for books and movies. Our maps are descriptive rather than prescriptive, and are intended to serve as boundary objects to catalyze conversations among designers, users, and stakeholders.

We might introduce this map by explaining that the marketplace has grown quite complex in recent years. In addition to in-store browsing, people can now search for books or movies from web, desktop, mobile, tablet, and kiosk user interfaces. Amazon, Blockbuster, Borders, Boxee, Google, iTunes, LibraryThing, MovieTickets.com, Netflix, Redbox, and the local public library are all participants with individual and often intertwingled products and services. A person’s criteria for choosing a provider may include: Cost, Time, Distance, Selection, Quality. Their process may feature several steps: Search > Select > Obtain > Use > Return. And, their experience may bridge multiple services, channels, and locations as they progress through this process. Now, let’s imagine some comments that such a map might provoke.

I like Redbox more than Netflix, because my desire to watch a movie tends to be spontaneous rather than planned. I often search and pay for movies at the office, and then pick them up from the kiosk along with some groceries on my way home.

I love how the mobile app let’s me search for nearby kiosks that have what I want. That’s great for when I’m out running errands and decide to rent a movie.

Netflix Watch Instantly works okay. I don’t have to leave the house, or wait for a download, and I can watch on my iPad while the kids play games on our TV. But the selection isn’t great, and there’s no way to limit searches to Watch Instantly movies. Sometimes, I get so tired of searching that I read a book instead.

I use the library a lot, because it’s free. I can search for a book or movie on the website, click the Request This Item button, and it’s delivered to the branch nearby. I get an email when it’s ready. The self-checkout kiosks work great. No waiting in line! And if I want to collect items late at night, I use the lockers.

You know how Amazon lets you Search Inside The Book? Well, sometimes when I’m at the library, I wish I could Search Inside the Library to find all the physical books and digital articles about a particular topic that I can put my fingers on right now. Instead, I have to search the catalog and a bunch of separate databases. It’s a pain.

Experience maps are great for participatory design. They get designers, users, and stakeholders all talking to one another and thinking outside the box. Speaking of which, it’s worth noting that in many contexts, search is a bridge application that connects experiences across devices and channels. It’s the ability to search on location and availability, for instance, that makes it possible to transform cars and bicycles from products into services. Ubiquitous service design demands that we re-imagine the patterns and possibilities of search and discovery.

The Intertwingularity

Mike Kuniavsky posits that the era of ubiquitous computing started in 2005 with the iPod Shuffle, the iRobot Roomba, and the Adidas 1 shoe. Back then, nobody foresaw plants that tweet, but we knew things were about to get weird as this passage in Ambient Findability shows:

My fascination with this future present dwells at the crossroads of ubiquitous computing and the Internet. We’re creating new interfaces to export networked information while simultaneously importing vast amounts of data about the real world into our networks. Familiar boundaries blur in this great intertwingling. Toilets sprout sensors. Objects consume their own metadata. Ambient devices, findable objects, tangible bits, wearables, implants, and ingestibles are just some of the strange mutations residing in this borderlands of atoms and bits.

Several years later, and this vision still feels right. We’re increasingly surrounded by smart things, but it’s not their intelligence that’s interesting. While the world waits for Web 3.0 and The Singularity, the real action has already begun. It’s called the intertwingularity.

It’s an era in which information blurs the boundaries, enabling multi-channel, cross-platform, trans-media, physico-digital user experiences. To succeed, we’ll need teams that are multi-disciplinary and individuals who can help us think visually. If we work together, the practice of ubiquitous service design will afford an intertwingularity that’s useful, usable, and desirable. The destination beckons, but the journey looks even more fun, for in the uncharted waters of futurity, it’s the map that makes the territory. Isn’t it time we set sail?

by Peter Morville