In recent years, my consulting process has become T-shaped, in part due to the gentle jabs of Peter Boersma, but mostly as a result of the fit between my expertise and the needs of my clients.

In the first phase, I conduct research (the three circles) and work with my clients to define a user experience strategy. This narrative expression provides a necessary but insufficient platform for design.

Figure 1. The T-Shaped Consulting Framework

In the second phase, I develop the information architecture, which requires specifying the structure and behavior of a web site, software product, or interactive service, so that users can achieve goals, complete tasks, and find what they need.

And, it’s this tangible expression of strategy, in the form of wireframes, sketches, and prototypes, that reliably translates an abstract vision into a well-grounded, actionable blueprint for design. Without that structural foundation, the strategy just hangs in space.

Frame Analysis

But this article is not about information architecture. Rather, it’s an investigation of user experience strategy, a novel phrase that’s crept into our vocabulary and is shaping our future. Let me explain.

The words we use to describe or frame our roles, our teams, and ourselves influence our own perceptions and the ways we are perceived by others. As George Lakoff explains in Don’t Think of an Elephant:

Frames are mental structures that shape the way we see the world. As a result, they shape the goals we seek, the plans we make, the way we act, and what counts as a good or bad outcome of our actions…Because language activates frames, new language is required for new frames. Thinking differently requires speaking differently.

In other words, user experience strategy is a term whose time has come, and while it leads us to better design, it also obscures our vision.

Don’t Think of an Experience

As an information architect, I’m sensitive to the fact that quite often the last thing users want is an experience. In many contexts, usability and findability simply outweigh desirability. Users want to find it, use it, and move on. The best experience is invisible.

In other contexts, we must beware the lure of end-to-end control invoked by user experience design. As Mark Weiser forewarned, seamlessness impedes invention. It’s seamful design that affords appropriation, co-creation, mashups, swarming, and other elegant hacks.

Of course, all terms have limits. Information architects must stay social and be wary of infoprefixation. And, interaction designers must heed the hyperbole that in design, interaction is the last resort. But these dangers don’t negate the real value that new terms deliver by helping us to think and act differently in unfamiliar terrain.

From Design to Strategy

Jesse James Garrett famously defined user experience design in a great diagram and an even better book:

Businesses have now come to recognize that providing a quality user experience is an essential, sustainable competitive advantage. It is user experience that forms the customer’s impression of the company’s offerings, it is user experience that differentiates the company from its competitors, and it is user experience that determines whether your customer will ever come back.

Similarly, Jakob Nielsen and Don Norman explain that user experience design “encompasses all aspects of the end-user’s interaction with the company, its services, and its products.” And, Nathan Shedroff positions user experience design as “an approach to creating successful experiences for people in any medium.”

A great deal has been written about user experience design but only recently has much ink been spilled on the subject of user experience strategy. I suspect there are a couple of reasons for the new focus. First, the elevated stature of user experience and design thinking in the business world have opened doors in the executive suite. Designers have a real opportunity to influence strategy. Second, we’re nearing an inflection point in an expanding set of markets, beyond which traditional product design is rendered obsolete.

Experience Ecologies

As we’re increasingly able to embed information and intelligence in physical objects connected via ubiquitous wireless networks, such concepts as open source, open APIs, mashups, co-creation, and findability are rapidly and irrevocably escaping the confines of the Web.

Adam Greenfield encapsulates the ensuing erosion of distinctions between “product” and “service” and the importance of “beautiful seams” in On the Ground Running, a brilliant piece that explores and eviscerates the iPod, Nike+, and Amtrak Acela ecologies.

Peter Merholz offers a valuable and complementary perspective in Experience IS the Product, and his partner Jesse James Garret, in a mesmerizing podcast on Experience Strategies, drives home the absolute imperative of designing from the outside-in.

Jared Spool positions what’s going on as a simple progression toward market maturity from technology to features to experience to integration. I’m sure Jared’s right, but this framing misses the real story. The way we conceptualize products, services, and brands is changing. We can glimpse the destination in Bruce Sterling’s spime and Julian Bleecker’s blogjects, but the journey has already begun, which is why we’re talking so much about user experience strategy.

Experience Executives

In the past, I’ve used the following quote to introduce the complex, intimate relationship between strategy and tactics:

In strategy, surprise becomes more feasible the closer it occurs to the tactical realm. – Carl von Clausewitz, 1832

Good strategy requires awareness of the full range of possible tactics. Richard Dalton captures this nicely in the Forces of User Experience, though I’ll never know why he chose a rainbow over a honeycomb.

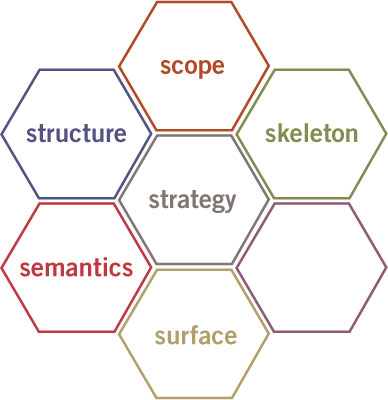

Figure 2. The User Experience Strategy Honeycomb

The key point is that within an increasing number of markets, executives can no longer afford to formulate strategy without embracing user experience, and to the extent their offerings include web sites, software products, and interactive services, these leaders (or their successors) must understand the complex interplay between strategy, scope, structure, semantics, skeleton, and surface. They must become experience executives, in concept if not in name.

It’s About Futurity

As Michael Raynor explains in The Strategy Paradox, strategy and futurity are inextricably bound together:

Most strategies are built on specific beliefs about the future. Unfortunately, the future is deeply unpredictable. Worse, the requirements of breakthrough success demand implementing strategy in ways that make it impossible to adapt should the future not turn out as expected. The result is the Strategy Paradox: strategies with the greatest possibility of success also have the greatest possibility of failure. Resolving this paradox requires a new way of thinking about strategy and uncertainty.

Raynor argues that to manage uncertainty, companies must build scenarios of the future, and identify strategies and strategic options for each possible future. I’d argue that those who develop user experience strategy would do well to embrace this framing in futurity.

For while our work certainly supports incremental progress towards better usability, findability, and credibility, user experience methods are equally well-suited to disruptive innovation. In the deep dives of design research, we gain insight into the latent needs of users, and with our sketches, mental models, and prototypes we bring greater richness and depth to the exploration of possible, probable, and preferable futures.

In short, we are futurists.

So, what about that empty cell in the honeycomb? Well, like our understanding of user experience strategy, the hive remains unfinished. We don’t have all the answers, at least not individually.

Perhaps we can fill in the gaps together, tomorrow.

by Peter Morville